Great leaders support innovation and know when to stop

Commercializing new products is all about managing risk, both commercial and technical. Great leaders understand that risks are inherent and that failure is part of the journey. They also know when to keep going and when to stop a project. Leadership involves celebrating both launched products and the failed programs. Knowing when to stop is just as important as deciding to move forward.

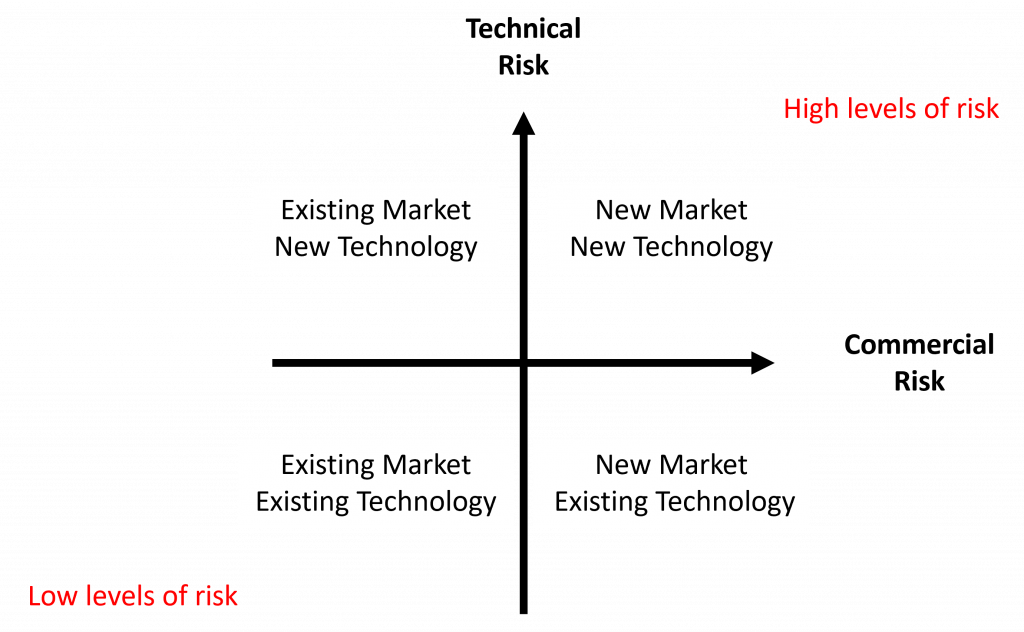

Visualizing Technology Risks

The risks associated with any technology can be visualized using the following graphic. Businesses are best positioned to sell existing products into existing markets. Small changes to existing products (line extensions) launched into known markets are easy ways to generate cash quickly. The development cost is typically low, and the commercial unknowns are minimal. The more risk, the bigger the bet and the bigger the effort – higher risk, higher reward. A business will typically want to move toward the upper right quadrant (new and exciting) to grow. The unknown of entering new markets with new technology sounds exciting, at least initially!

Most of my career has focused on front-end innovation. It’s fun and challenging, yet it comes with risk. I’ve failed several times to commercialize new technology and witnessed large programs fail, sometimes after many years with large teams and budgets. This blog post captures why I think some of these innovations failed. Here are some common pitfalls that can lead to product development and launch failure.

Assumptions about the market or the need

Form hypotheses and constantly try to invalidate them

Both commercial and technical teams need to form hypotheses early and constantly pressure-test them. Unvalidated assumptions compound launch risks as time and investment increase. Failing to pressure-test hypotheses about market trajectory, customer needs, and value chain players poses a greater risk than unvalidated technical hypotheses.

The more unknown the market, the more optimism about the “what if” grows. This unknown can easily be spun as, “If we capture just 1% of this market, revenue will be X based on market size.” This approach is a good initial estimate but isn’t founded in reality. It’s akin to saying there’s a big pot of money at the end of the rainbow!

Constantly validating and revalidating commercial assumptions is essential. Ideally, validate the commercial hypothesis before entering the lab. However, a prototype is often required first. Minimizing the upfront technical effort is key.

The best way to invalidate a hypothesis [yes, I meant invalidate – we are here not to have confirmation bias] is to conduct Voice-of-Customer (VOC) interviews. Present people with visual aids and descriptions to give them something to react to. After building initial prototypes, test them with consumers and others in the value chain. This process of building better prototypes and validating the market provides a feedback loop. New insights will emerge.

Changing market dynamics

Developing a cool product where there’s a market gap is great, but someone else might be developing a similar solution. I invented a cool new technology for insulation contractors years ago. Our solution offered a new, lower-cost option. While cost-effective, it wasn’t simple and elegant, though functional.

Shortly after we finished development and were market-testing, a shift occurred. A well established market leader developed its own lower cost option. Their solution cost slightly more than ours, but their advantages were multifaceted. They occupied a different part of the value chain as the leader, their solution was more elegant, and they had greater credibility. Ultimately, our technology was shelved.

Trying to scale too quickly, draining the cash

I’ve witnessed major programs fizzle after large amounts of cash were dumped into high risk programs (new technology, new markets). The goal was rapid business and technology growth. The rapid cash burn consumes any future program value, eventually requiring the program to be shelved.

Some markets need to be built, like the EV market. In 2008, the Obama administration pushed to grow the electric vehicle industry, investing $2.3 billion in large battery manufacturing plants. The market wasn’t ready. It took about ten more years for EV manufacturing momentum to pick up. Even now, only a small percentage of vehicles on the road are EVs.

Forming markets often requires new technology. The barrier to entry for new technology in these unformed markets can be low due to low standardization, uncertain costs, and low regulation. This sounds attractive, but if the supply chain isn’t set up and the value is uncertain, pumping cash into the technology to “scale quickly” wastes money. Building the market and technology together should be the goal because building the value chain, changing buying habits, etc., takes time. This means funding development over a long period, possibly 10-20 years.

Technical challenges slowed adoption

Technical and commercial challenges always exist. When developing new technology, the objective is to validate its performance against the commercial hypothesis. In software, this is easy with updates. With physical products, the process starts with concept drawings, then simple prototypes, expensive prototypes, and finally initial production runs.

Technical challenges create barriers to adoption. Customers might like the product, but others in the value chain might not, delaying adoption. Creating a grid of the value proposition for all players is essential. Equally important is listing the reasons for non-adoption by each player.

Being willing to pivot the technology

Developing consumer and industrial products requires a commitment to R&D before commercialization. Breakthrough innovations require more Research and less Development (Big R, little d), whereas adjacent product innovation requires less research and more Development (little r, Big D). Both require both research and development.

Commercial development must follow a similar journey. Being willing to pivot or stop is important. Understanding the technology and market dynamics is crucial for knowing if the technology can or should be revised later. Knowing when to pivot is key. Signs a pivot may be necessary include: changing market conditions, insurmountable technical challenges, or a shift in customer needs. A pivot can involve changing the target market, the product features, or even the underlying technology. The key is to remain flexible and adapt to new information.